My brother and I grew up in a military family. We knew the names of the battles depicted in Band of Brothers, Black Hawk Down, and Generation Kill before we knew how to write our names. We grew up listening to war stories from our uncles about battle worn 20-year-olds setting complex ambushes and stalking Vietcong through unsurmountable jungles.

The image I built in my mind of how a soldier should be, act, and look was physically and mentally tough; built to go into wild spaces and face death with a stoic determination. I believed every service member faced their baptism of fire and returned changed—saturated in a suppressed silence that only comes from witnessing the capacity of human brutality.

I watched too many movies.

In reality, most of the military supports a few combat jobs, and even securing a combat job does not guarantee you will see combat. I spent seven years on active duty in the Army as an infantryman during the longest period of war the US has ever been part of, and yet more of my friends have died by their own hands than any enemy combatant. Veterans are 57% more likely to commit suicide than their civilian counterparts[1] and while it’s tempting to write the suicides off as simply a complimentary byproduct of the brutal reality of war—the strange truth is few in the military have the chance to experience, let alone witness the horrors.

Even during the last 22 years of the Global War on Terror, only about 10% of the military has seen combat[2]. So, if it’s not the horrors of war that are causing this, then why are so many veterans seeking that final solution?

The military prepares it’s service members to face all enemies “foreign, and domestic” through an indoctrination into military culture. However, we are expected to shed this indoctrination on our own and immediately rejoin civilian society as fully functioning members. Without recognizing what we lost in the transition, we can never hope to regain the sense of fulfillment the military gave us. There are many reasons why veterans choose to take their own life, and I don’t claim to even have totally conquered my own demons, let alone be any sort of authority on veteran suicide. What I do know is that the human mind is not built to survive the paradigm shift we experience when we stow away the uniform. At least not alone.

When you ask a service member what their plans are when they separate, most will respond with what job they have lined up, or what career they hope their GI Bill will help them get. While the financial hardships inherent to any career change are a valid concern, more attention needs to be paid towards equipping service members to adjust to the emotional battle we all eventually face in normal mundane life. I believed since I had not seen combat that I would be able to amputate the Army from my personality like an infected limb. It’s just another job, I told myself. Just, move on. It took me three years to realize that it’s not just the job that I lost, but my sense of belonging, my purpose in life, and my stable identity.

It’s been five years since I stuffed my uniforms in my garage, and there have been many times that I have stared off the edge of the cliff and considered the relief that many of my friends saw. The only reason I haven’t taken that leap is because I found a new community in the family I developed, a new identity I could be proud of, and a new purpose in life that gave me fulfillment. I am not a politician, and I currently have about as much power when it comes to military policy as I did when I was a cherry machine gunner ready to jump out of a C130. I cannot change how the military helps their veterans put away their uniforms; all I can do is try to share some of the lessons I’ve learned through this process with the hope that someone will get something from it. I know the suicide rate of veterans will never be zero. Still, until we can figure out how to prepare veterans for the emotional war we all inevitably face, more and more of us will continue to seek that final solution to their temporary problem. I am tired of going to funerals, and I am tired of seeing my family suffer through this process. Something has to change, and while we are not alone in this battle, we are our greatest advocate.

BELONGING

I left my home in Portland, Oregon for Fort Benning, Georgia only two months after receiving my high school diploma. Aside from my few friends on the wrestling team, I was a comfortably solitary teenager who would take a night alone in my room over spending it with a group nine times out of ten. It wasn’t that I didn’t like other people, I always just felt most comfortable alone growing up. That was the first thing the military took from me.

Thinking back over the next seven years of active duty, the only time I really felt like I was doing something on my own was when I was preparing to leave the service. From the initial medical exam to my final training exercise, I was always around others, and this developed a reliance on a community. This is intentional, and is the key to our military’s success: everyone values the lives of those around them more than their own. This transformation from an individualistic to a collective mindset is best described as an indoctrination, or “brainwashing” into military society, and is the guiding motivation behind basic training. This indoctrination rewired our brains to no longer see ourselves as lone figures, but as a small portion of the world’s largest gang where survival depended on cooperation. This collective thinking only grows stronger the longer you are in, and the intense, stressful events you go through only work to make that bond more permanent.

I have never felt safer than sleeping in a 60×20 foot room full of bunk beds with 50 other soldiers, all of whom I know would charge headfirst into a burning building if they knew I was trapped there. It’s hard to find that kind of community outside the military, and it makes transitioning feel lonely. At every job I’ve worked at since my service, I’ve searched for that dedication and feeling of community where I know I could entrust my life to those I’m around. I realized how unfair of me it was to expect that level of dedication because the stakes at civilian work or school will never be as high as they were in the military, and my coworkers don’t hold that same expectation of me. This was a tough pill to swallow, but one that every veteran faces when they leave the service.

My first year off active duty was challenging, but I stayed in Colorado Springs and roomed with my best friend Lamar to try to postpone the loneliness I knew would eventually come. The first few months I still hung out with my military friends, going to bars and parties with the fervor of a seasoned addict. Within six months, my old unit deployed to Syria—taking all my friends with them. I was finally truly alone. I had no desire to move back to my hometown and still didn’t feel like a student. I struggled to connect with people I met in college, hell, I graduated high school when most of my classmates were in second grade. I missed feeling that brotherhood with everyone I was around, and yet I made no attempt to give people a chance. I stuck to talking with other vets because I felt they understood me. It wasn’t until I got a job at the university newspaper that I realized I had more in common with theses “kids” than I imagined, and now I realize how many opportunities my pride made me miss.

Every new chapter in my life is a process of gaining and losing friends. I think of it as a filter for building my family. When I left the military, I kept about as many friends as I did when I graduated high school— the same goes for new schools, new jobs, and new neighborhoods. I developed relationships with locational friends with the hope that maybe a few will join my growing tribe. While my community shrunk when I separated, I wasn’t limited in people I could count on. It took me too damn long to realize I was the only one in control of building my community, and that I wasn’t cursed to wander the halls without feeling a sense of connection with my fellow students. While I may never feel that large connection again, I found a more valuable and long-lasting bond with new communities.

IDENTITY

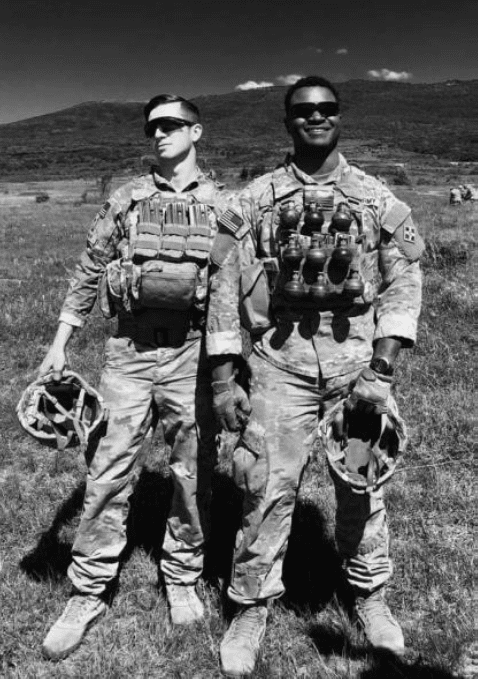

Missing a combat deployment on active duty left me deeply resentful, and unsatisfied with how I served. I felt shame when I told people I never deployed, and I felt like I didn’t even deserve the title of veteran since I had never actually done the job. I had one deployment to Eastern Europe in 2017, which was more of a 9-month drinking-then-training tour than what Hollywood has conjured in our minds of a military deployment. Being an undeployed infantryman feels like spending the best part of your twenties in med school then getting a job as an electrician once you finish. I never had that “baptism of fire” that would validate my capability, and it felt like something I was never going to obtain.

Once I reached the crux of my service and realized I wouldn’t get the deployment I wanted on the other side of it, I felt ashamed. I knew I was done with the regular Army, and I still had an emptiness inside me I thought could only be filled with war. I signed up to try out for a National Guard Special Forces unit based outside of Denver. I knew I had the best chance of finally getting a seeing combat if I was a Green Beret, and I was willing to push through another two years of training if it would get me to see combat.

I failed. Miserably.

The first step to the two-year Special Forces Qualification Course (Q-Course) is a three week selection process which includes hundreds of miles of running, rucking, and swimming—most of it with a 60-pound ruck sack on your back while accomplishing various other physically and mentally stressful tasks, all designed to weed out the unprepared and undedicated. 50-75% of candidates do not get selected, so most units conducted their own three-day assessment to test soldier readiness. I never had an issue with the physical aspects of the Army, and I craved the accomplished feeling after completing a challenging event. I believed I would always be capable enough to push my body when I needed to, but a half decade of abuse began to pile up, and I crumbled at the end of the weekend. I found myself in the hospital Monday morning with feet the size of butternut squash, unable to walk or move from the pain.

When I was laying in the hospital, Lamar sitting in the chair at the foot of the bed after carrying me down to his car at 3 a.m., I finally accepted that I was done with the Army. While my feet healed quick, I started to notice the charcuterie spread of injuries that came and went with the weather. That weekend was my last chance to chase a deployment, and it showed me I could no longer do the physical aspects of the job. A few months later I walked into my boss’s office as Sergeant Baker, he handed me my separation orders, shook my hand, thanked me for my service, and I walked out of that building as Mr. Baker, with no intentions of ever looking back.

Aside from the loss of community, veterans also lose their sense of identity when they separate from the military. During that initial indoctrination phase, part of becoming a collective member involves taking on the identity of a soldier, sailor, airman or marine. That begins with your uniform. Everything in basic training was uniform—same haircuts, boots, shirts, jackets, beanies, socks, even underwear. Everyone was the same because everyone needed to look the same. It was the first step to taking on that identity, and was what initially brought you into the fold of the group. During the duration of training, you shed the skin of the civilian, and you grow the new one of a soldier. You wear a soldier’s uniform, you march like a soldier, they even make you eat like a soldier. Everything you do is meant to reprogram how you view yourself so you can fit into the massive machine of the United States military. You are taught to stand up straight, speak with a commanding tone, and be proud of the new person you have become. You are told how valuable you are to society and how grateful everyone is for your sacrifices. When civilians find out you served, they almost instinctively thank you for your service, which only works to boost this image you’ve built in your mind of what a soldier is. When you separate, that all disappears.

The day after I left the office that final time, I emptied out all the military gear I had accumulated over the near decade of service. I kept some of the sentimental stuff like my dog tags, unit patches, and the field blanket I’d slept with the last seven years. All the extra gear I gave away to friends, and all my uniforms went to Goodwill. I kept one set of fatigues and my dress uniform jacket that are currently in a trash bag sitting in the bottom of a tuff box somewhere in my garage. I wanted to keep the memories, but I wanted to purge the military from my identity. I didn’t want to be one of those veterans that only talks about what they did in the Army, and seem to be unable to move on from a past life.

While what veterans go through and accomplish is extraordinary, for most of us it’s such a small facet of our lives that it does more harm than good to keep our identity attached to it. If anything, it keeps us from growing and we remain trapped in a life we no longer are a part of, and that has long forgotten us. The position I left in the military was filled before I was off the base, and by now the last person in that building who would recognize me has long left. By getting rid of everything that connected me to that identity, I felt in a way it was shocking me out of my indoctrination—almost an undoctrination. I did everything I could to hide that I served, either being vague or straight up lying about what I did from age 18 to 26. I don’t do this anymore, but I feel like now I’ve developed a new identity that isn’t centered around something as impermanent as a job I volunteered to do. While my past is no longer the focus, I feel I’ve had a reckoning with it where I recognize that my time in the military has shaped who I am today, but it doesn’t define who I am.

I will never be able to completely let go of who I was in the military, but instead of giving in to holding onto a past life, I think its more important to have a reckoning with the past, and recognize the importance of it while also moving on to the new person I’ve become. I want to use the metaphor of “shedding the skin” of my former self, but that makes it seem like I am trying to forget what I experienced by throwing it away. That’s impossible. The life I’ve experienced made me who I am, and I think it’s more akin to patching the holes in my old self with who I have become. Once that happens, you find your new identity.

PURPOSE

I grew up in a strict fundamentalist Christian community where, from as early as I remember, I knew I would grow up to become a pastor. Everything I did, from clubs I joined, to classes I took were directed towards making me the best Christian leader I could be. Even my motivation for joining the Army intertwined with becoming a stronger shepherd for Christ. While those beliefs changed, and my life took a different path, I again found myself in an environment where my occupation and purpose were so intertwined I couldn’t distinguish the two. As a child, I was a Christian, and my purpose was to be the best Christian I could be. As an Infantryman, I was a soldier, and my purpose was to be the best soldier I could be.

If only life consistently echoed that same simplicity.

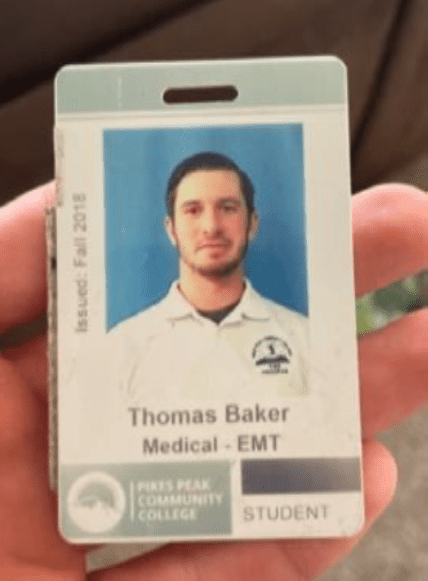

It took me three years after I got my separation orders to realize I was innately trying to mimic this unity by finding a purpose in life through my next occupation. I’m not saying it’s impossible to find a career that gives a sense of fulfillment, and with the average person spending 40 of their available 168 hours per week at their job, we all hope to find an occupation that makes us feel like we are doing what we are meant to do. I signed up to start EMT school the month after leaving the Army, figuring being a first responder would give me the same sense of purpose. My body continued to break from the work and the measly ambulance pay encouraged me to switch my major to nursing. Though I wasn’t as frontline, I still felt on track to a fulfilling career that filled the void left by the military. Being the best nurse was my new purpose, and I would see it through…until a wall called General Biology jetted up between my perceived purpose and my academic abilities. I could barely pass my science prerequisites, and COVID had limited my world to the four walls of my apartment. I lacked the self discipline for online school, and I failed that semester in spectacular fashion. So bad that I dropped out and got a job as a salesman for Progressive Insurance. I knew selling insurance wasn’t my purpose, but I thought maybe I could find it in my free time.

I never did.

During the next nine months that I worked at Progressive, I acquired a daily routine of spending the thirty minutes before my shift using everything from meditation to alcohol to convince myself that it wasn’t worth it to sell everything in my house, buy a van and go live by some river. I may have been poor, but I would be happy and free of that soul-languishing existence. I would find myself standing behind my desk, staring far past the login screen into the bottomless void I saw my life falling into. I didn’t have any hobbies besides smoking, and I never actually pursued any of the passions I told myself I would when I dropped out of college. I don’t think I was ever closer to taking that leap over the edge than I was here, and those thoughts are what motivated me to make a change.

I don’t believe in pre-destination, and I still don’t believe each person has a singular purpose that they must achieve to be “satisfied” with their life. Purpose was easy in the military because I just did what I was told. I was told where to be, when to be there, what to wear, and what to do once I was there. Everything is laid out in front of me with the instruction manual highlighted and tabbed for easy reference. I needed that secure sense of direction and the confidence I felt from knowing I was on the right track towards something I wanted.

I’ve heard a metaphor describing purpose as trying to navigate to a point using a map and compass. Your purpose is to get to your destination, and the map holds your plan of action. A “compass check” in land navigation is where you stop moving and look at your compass and surroundings to make sure you’re still heading in the right direction. I knew I wasn’t heading in the right direction before, and while I appreciated the financial security Progressive provided, I knew it was not where I was meant to be. And while I love the romanticized idea of being in the medical field resuscitating patients from the dead— I suck at science, and I have no desire to endure the agony I saw coming from continuing to pursue a life engrossed in human biology.

At the start of that journey, I expected my new purpose to be a job, but what I found was that my purpose is more than just what I do for money. It’s a more profound desire for true meaning in my life—a fulfillment that can only come from doing what I know I was meant to do all along. I also expected to have a more concrete understanding of why I’m on this enormous hunk of earth flying through the cosmos, but sometimes life gives me a hint and I just have to wing it. I no longer believe purpose is a static entity; it is something that evolves as we progress through life. I’m still searching for that dream career that will fill all the boxes I hoped for as a child, but I’m no longer relying on that anymore to fulfill me. I want to do something that helps people, and I want to write. The rest I’ll figure out through my compass checks.

Tom Baker is an airborne infantry veteran and current creative writing graduate student. His passion for writing began during his reintegration into civilian life, where it has been an instrumental part of his healing process. This experience drove him to become a teacher with the hopes of sharing this with others. He currently lives in Pensacola, Florida with his wife Samantha and their 3 pets.

Chris

Good read Brother !

David Herrera

This is really good.

I also am a non combat combat arms veteran who still struggles over fifty years later with the fact that I did not see combat. I can relate.