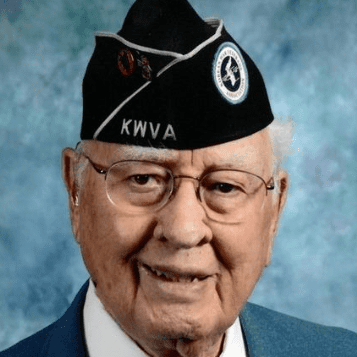

Lt. Col. Scott Defebaugh (1923-2022) was a WWII Veteran I met while visiting the retirement home where my parents live. Over a series of interviews in March-June of 2022, I learned a small fraction of Scott’s story. I have chosen here to write in the first-person from Scott’s point of view, switching to first-person in my own point of view (the bolded text). It’s a way of writing I’ve never tried before, and I’m hoping that this style of writing might give readers a sense not only of the dialogue that went between us, but also what we may have been thinking as we chatted together. A few months after he passed away, his daughter, Melissa Defebaugh, wrote this foreword:

Dad was an army medic serving at a Field General Hospital (MASH) on the Salisbury Plains

of England. One night, he went to a town dance with some of his buddies. After missing

his ride, later that night, he decided to walk back to camp.

On the way back, he stopped to soak in the sight and peaceful quiet of Stonehenge in the pre-dawn hours.

The silence was broken by a droning from above. He looked up in the sky and saw the greatest air armada of all time.

IT WAS D-DAY!

Years later, he gave me a bag with a pair of his combat boots. They were dust covered and

grimy. The soles were caked with dried mud which surprised me as I was used to his spit-

polished boots.

“These were the boots I was wearing on D-Day,” my dad said. “Don’t ever clean

them….there’s history on those boots.”

I met DeLyn Winters on a clear June day just a couple of months after my 99th birthday. Her mother, a fellow resident in my retirement home, introduced us. She told me that her daughter worked with veterans to tell their stories, and she wanted to help tell mine. I was skeptical; although I served in both WWII and in the Korean War, I hadn’t seen combat. There aren’t many vets like me left, and young people today seem to expect all vets’ stories to be overly dramatic. I think our stories, even the ones without drama, like mine, need to be told so people know they aren’t a movie.

Scott Defebaugh did not look to be nearly 100. He looked high 70’s, tops. He greeted me with enthusiasm. After I sat down and brought out my laptop, he said, “you’ll have to stop me when I’ve talked too much. I tend to do that.” I laughed and stretched my fingers. “Bring it on,” I said.

I went into service in February 1943, medical basic training to be exact. Six weeks later I was promoted to Private First Class. Basically, I just learned to clean bedpans. I got assigned to a base in Hot Springs, Arkansas where I reported to the hospital and got assigned to the “psycho ward” as we called it back then. That’s where I learned to spell psychology, and to value the nurses, my two most valuable lessons. Then I got assigned to Camp Robinson, a German POW Camp, but I had a problem: I didn’t speak German! There was no fence around the compound yet because there were only five POWs, so I stood in front of them and said, “I’m going to be your caregiver. Want to eat, want anything? Learn English.” One German soldier, Rudolf, acted as an interpreter and became my friend. A few weeks in, Rudolf was waiting for me when I showed up with food. He told me the two guys at the end were SS, and he would take care of them. I was relieved! And secretly I laughed—Rudolf made sure they didn’t get seconds on the chow.

After the war I was discharged from the Army but I wasn’t done serving, so I joined the Reserves, and that’s where I served the majority of my military career. Over time I ended up as Ward Master in the isolation ward, where I dealt with a lot of cases of soldiers near death, so telling family someone had died or was dying was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done. One of my most memorable cases was a young man with a large piece of shrapnel embedded in his head. We all knew it was only a matter of time before this guy passed. I used to sit with him to watch him, but what really got me was glancing to the side table where I saw his wallet. A picture of his wife and small children was there, propped next to it where he could see it. That was a hard one, but it taught me to distance myself from the trauma and to focus on helping the patient and their family during such a difficult time.

I guess I have a way with people, because soon I became the go-to guy to watch over dying patients. Those of us who worked on the ward were expected to update the next nurse when our shift was over, telling them the patient’s stats and condition. I became good at estimating when a person might pass away, and no way did I want it to happen on my watch. We developed a code: if I came in and the patient had a penny on their foot, I knew their time was near, and I always dreaded that—but I always kept a few cents in my pocket just in case I needed to signal the next person.

One time I had been sitting with this young man for several hours, and I knew he was getting close to his end. I closed my eyes, I spoke to him, and I prayed. He was still hanging on when my shift was over, so I said a few parting words, reached into my pocket for a penny and slipped it onto his toes. When I came back the next day, a new patient was in his place.

You know, you become sort of inured to death when you see it as often as I did. I have to say, being around dying people sure made it easier to deal with deaths in my own family. It wasn’t such a shock, in some ways. I sort of knew what to expect in the grieving process; having spent years distancing myself was good practice for when it happened to people around me. I also know what to expect when my own time comes.

I saw Scott again about a week later, on Father’s Day. He was sporting a huge bruised eye. When I asked him what happened, he said, “You should see the other guy!” After a chuckle, he told me he’d fallen against a table the day before. Two days later, to my surprise, he was gone. The injury had been enough to compromise his already fragile immune system.

I learned by attending Scott’s funeral that he had two families. After his first wife passed, he got married again and was immediately adopted by his new wife’s grown kids. As I sat off to the side during the service, it was comforting to see both families: his own two children and their kids and grandkids, and his four step-children and their kids and grandkids, chatting and laughing with one another. After recounting his long and illustrious career, the minister invited people to share a few words about Scott. So many people had anecdotes and stories to share that we ran out of time before people ran out of stories.

I left his Celebration of Life without going to the reception afterward. I was overwhelmed by the scope of Scott’s life and service. To me he was such a humble person; I had no idea until I read in his obituary that in addition to 40 years of military service, he was the Executive Director of the USO in Columbus, Ohio, he opened the first office of the American Cancer Society in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that he was an Executive Director of the Easter Seals Society of Milwaukee County in Wisconsin, or that he volunteered with the Red Cross for another 19 years at Evans Hospital in Fort Carson after he retired. How could one person do all that? Even though it lacks the drama he said qualified a “good story,” Scott’s life would make a wonderful movie. It’s a story of a life well lived.

Tim Bigonia

DeLyn,

Thank you for sharing Scott’s story. I attended school with one of Scott’s sons and became aware of how incredible Scott was through out my high school years. As I recall Scott always made time for whatever was needed. No matter how large or small, Scott was there to help, make something happen, or fulfill a need. His warmth and talkative personality was refreshing for this high school kid, as he was one of only a few at the time who talked to us teenagers, instead of at us.

Your story revealed so much I was not aware. I always knew Scott’s backstory was layered and extensive, but I never appreciated how much. He will be missed and was missed after high school as life gets away from us and distance becomes an excuse. My regret was never reaching out and making certain I reconnected.

Thank you again for your story.

Tim Bigonia

David Herrera

And a life lived well.