We have lost one more World War II veteran. Richard L. Walker, born May 7, 1924, passed away on October 26, 2020. Son of William Walker, M.D., one of the first black physicians in Colorado Springs, Richard walked the body-strewn Normandy beach with his battalion on a forced march to Cherbourg shortly after D-Day, June 6, 1944. After the war, Richard completed a degree in chemical engineering and worked at Holly Sugar Company for many years, and was one of the pioneer scientists who developed brown sugar. Here, in his own words, as told to Lucy Bell in 2019, is his story.

***

June 6, 2019, marks the 75th anniversary of D-Day, the day the Battle of Normandy began in 1944. 156,000 American, British and Canadian forces landed on five beaches along a 50-mile stretch on the coast of France. The American troops landed on code-named Utah and Omaha beaches. The invasion, one of the largest amphibious military assaults in history, played a significant role in ending World War II.

As the years pass, fewer and fewer veterans remain to share their memories of being there during that historic time. But one such veteran, 94 year-old African American Richard Walker of Colorado Springs, remembers it well.

In November, 1942, the Selective Training and Service Act lowered the age requirement from 21 to 18, making men from 18 to 37 years old eligible for the draft.

But not if you were black. Blacks were passed over for the draft because of racial assumptions about their intellectual status and the ability to follow orders.

Richard, son of Dr. William Walker, one of Colorado Springs’ first black physicians and Edna Deason, Colorado College graduate whose family had resided in the city since 1909, had no draft orders hanging over his head. He was enjoying college life at his father’s undergraduate alma mater, Kentucky State College.

But in 1943, as the war effort grew, and the need for more troops increased, the racial assumptions, though still believed, were side stepped.

Blacks were now drafted, but not considered eligible for combat duty. They were assigned to “labor units,” at best involving construction and transport, at worst, peeling potatoes and shining shoes. More than one and a half million African Americans served in the US military in WWII. However, this Greatest African American Generation faced unequal treatment and limited opportunities for promotion. Strict segregation prevailed in housing, meals and activities. Even the blood banks were segregated.

Back in Kentucky, 19 year-old Richard Walker saw his college plans put on hold, when he received orders to report for basic training at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland. The black recruits tested the safety of gas masks, going into chambers filled with chlorine gas.

After field training in Camp Lee, VA, Richard boarded a large troop ship that followed a zigzag course across the Atlantic to avoid German submarines.

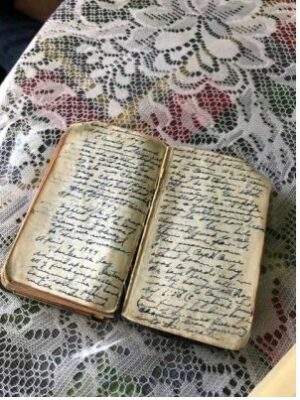

Richard’s parents had given him a small Bible with the words, May This Keep You Safe From Harm inscribed on a metal-plated cover. He filled the blank pages in the back with a diary of his ten days at sea and kept it with him on his body 100% of the time.

Destroyers equipped with sonar technology went ahead of the troop ship, detected enemy submarines and destroyed them with depth charges, saving the lives of the soldiers many times.

“I guess we’re going to England,” Richard commented to his buddy when on the tenth day out everyone was given a booklet titled “A Guide to Britain.”

They landed at Southampton Harbor on April 22, 1944. From there they were sent to Weymouth, England, on the southern coast, directly across from France. Its deep harbor provided the jumping off place for the D-Day invasion, though no one knew about that until the day it happened. Over 500,000 troops would depart from this location over the course of the war.

Richard’s battalion had comfortable lodgings at this seaside village where the friendly residents welcomed the black American troops. They even enjoyed English pastries from a bakery down the street.

A few weeks later a battalion of white troops arrived in Weymouth and trouble erupted. The new U.S. arrivals were from the South, and not happy about serving in equal positions with black soldiers. Name calling led to fist fights that grew into altercations in which the younger males in Weymouth joined in on the side of the black soldiers. Richard was one of the newer recruits and didn’t take part in this, but in later years, found it ironic that on the very eve of one of the most massive invasions in military history, black and white Americans were fighting each other in the streets of this English village.

Richard’s battalion was not called into action until after the Fall of Cherbourg, which freed the French city from German occupation on June 27, 1944. They left Weymouth and landed on Utah Beach.

The battalion needed to get to Cherbourg as soon as possible. Supply ships were beginning to reach the dock, and Richard’s battalion had to get everything unloaded and on the move to the Allied forces who had already begun the march across central France, headed toward Berlin.

To meet this deadline, Richard’s commander ordered a forced march to Cherbourg. A forced march is, by definition, a military movement that is at a faster pace, a longer distance, and under more adverse conditions than a regular march.

Richard remembers stepping over comrades who had collapsed from exhaustion. Even though he was carrying a 95-pound backpack, he was young and strong, and able to keep up. He saw remains of bodies on the beach–casualties from the D-day battles, over a month before. Body recovery was ongoing, a horrendous task, and the grave battalion was an assignment no one wanted.

The forced march stopped for the night in pouring rain, and the troops dug foxholes in the mud using their helmets for pillows. The next morning they let the rain wash the mud off their outer clothing. Trucks picked them up and they drove through the countryside enroute to Cherbourg.

They passed through St. Loo, and Richard has never forgotten the sight of the complete destruction of this French village. Only one chimney remained standing. The Allied campaign had leveled the town to clear the area from German military occupation.

The troops living quarters were adequate but they were getting tired of the same old army rations, when they heard good news. The next supply ship scheduled to arrive had fresh meat onboard and they would soon be feasting on hamburgers, and pork chop dinners.

The day of the ship’s arrival, they were preparing to head for the dock to unload it, when a huge explosion rocked the barracks. An undetected German submarine had bombed and sunk the ship just as it neared port. Richard and his comrades were issued wading coveralls and sent in water up to their necks to recover the drowned and the injured. As usual, Richard took the metal-plated Bible with him, this time tightly wrapped and tucked into a top pocket of his waterproof overalls. When they’d safely rescued the survivors, they went after the prized fresh meat packages that bobbed along on the waves. They only recovered a small part of the cargo, but they did eat well for the next few days. Other supply ships docked safely and Richard and his comrades spent many days transferring supplies onto waiting transport vehicles.

After completing their mission in Cherbourg, the supply support battalion disbanded. Only Richard and his commanding officer were left to inventory the remaining supplies and send them to a secure depot in Nice, France.

Richard was sent to Liege, Belgium, on the border of Germany. Belgium had been under German occupation since May, 1940, when the Belgian king, Leopold III, surrendered to the German forces.

Many AWOL soldiers filled the town, surviving through criminal activities. Daily street violence was so common, it was not safe to be outside. When a tracer bullet with a red trail flew past, inches from his face, Richard decided it was time to get out of there.

He had enough points to receive his honorable discharge and sailed for home. The ship was new and luxurious compared to army standards and the trip took only three days, since dodging U-boats was no longer necessary. The ship sailed past the Statue of Liberty and docked at New Jersey for the final discharge requirements that allowed him to board a train to Colorado.

His train pulled up at the Colorado Springs Depot that in later years would become Giuseppe’s restaurant. Not allowed to tell his family ahead of time about his arrival, Richard walked the several blocks to his parent’s home on Corona Street. Needless to say, a joyful reunion took place. The metal-plated Bible made it back unscathed.

In the years that followed, Richard married, and raised a family of two sons and one daughter. His daughter followed in her grandfather’s footsteps and became a medical doctor.

Richard completed his degree in chemical engineering at Kentucky State. He joined the research lab at the Holly Sugar Corporation in Colorado Springs, and worked with the team that enabled Holly Sugar to develop brown sugar, a new product for them.

Richard’s memories include many extraordinary experiences: Dodging U-boats determined to sink the troop ships, the forced march past the bodies of the D-Day dead, the water rescue of a sunken supply ship, and the everyday challenges of being a soldier in wartime. Dressed in a crisp striped shirt and navy jeans held up by natty suspenders, Richard sits comfortably on his living room couch with Gwendolyn, his wife of 57 years beside him. He smiles and says, “Looking back I see that I’d been through some demanding and dangerous times. But when I left for the war, I was 19 years old, and to me, it was all a great adventure.”

Acknowledgement: This story is part of a larger article, titled “At Home and Abroad,” previously published in the Winter 2019 edition of The ALMAGRE REVIEW: Issue 6. Publisher and Editor: Joe Barrera. thealmagrereview.org

***

Lucy Bell’s 35-year teaching career included over twenty years as a writing consultant. Her latest book, Coming Up, A Boy’s Adventures in 1940s Colorado Springs, combines narrative non-fiction with the history of the black community of Colorado Springs. It features rare historical photographs and the watercolor illustrations of Linda Martin. Release date: October 14, 2018. Her children’s novel, Molly and the Cat Who Stole Her Tongue, published in 2016, is available at Poor Richard’s Bookstore, Colorado Springs and Amazon.